Thinking Space

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and the Barcelona Pavilion: An Introduction to Architectural Thought

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe occupies a central position in the history of modern architecture not only because of his formal innovations, but because of the way he redefined what architecture could be. His work represents a shift away from architecture as an object of representation toward architecture as an act of thought, where space, structure, and material operate together to construct meaning. Rather than pursuing expressiveness through form or ornament, Mies sought clarity through reduction. His buildings are not meant to impress through excess, but to reveal their essence through proportion, precision, and presence. The Barcelona Pavilion stands as one of the most distilled and instructive expressions of this approach, functioning as both an architectural work and an introduction to Mies’s broader way of thinking.

Conceived for the 1929 International Exhibition in Barcelona, the Pavilion was designed as a temporary structure to represent Germany in the aftermath of World War I. Despite its ephemeral intention, it became one of the most enduring and influential works of modern architecture. This paradox is central to understanding Mies’s work: a building meant to exist only briefly manages to articulate ideas that transcend time. Rather than functioning as a conventional exhibition hall, the Pavilion operates as an architectural manifesto. It does not display objects; it constructs an experience. Through space, material, and movement, Mies presents a vision of modernity rooted not in rupture, but in continuity.

This continuity is especially evident in the Pavilion’s material language. Mies combines glass and steel—materials associated with industrial progress and modern construction—with various types of marble, a material historically tied to monumentality and classical architecture. This juxtaposition is not accidental. It reveals Mies’s deep engagement with architectural history and his refusal to erase it. Marble, traditionally associated with mass and enclosure, is reinterpreted here as surface, reflection, and plane. Its role is no longer structural, but spatial. In this way, Mies abstracts history rather than rejecting it, demonstrating that modern architecture can emerge from tradition without imitating it.

Materiality in the Pavilion is never decorative. Glass, marble, water, and steel work together to construct a continuous spatial experience rather than a fixed object. Light reflects across polished surfaces, dissolving clear boundaries between interior and exterior and creating a space that is constantly in flux. The Pavilion cannot be understood from a single viewpoint; it reveals itself gradually as one moves through it. Architecture unfolds in time, shaped by perception, movement, and reflection. The building behaves less like an enclosure and more like a sequence, where each step produces a new spatial relationship.

The structural logic of the Pavilion reinforces this experience. Slender steel columns liberate the walls from their traditional load-bearing role, allowing them to function as independent planes that guide movement rather than confine it. These planes create subtle alignments and visual connections, encouraging a continuous flow through the space. The low horizontal roof further frames the human body within the architecture, sharpening awareness of proportion, material, and detail. Rather than overwhelming the visitor, the Pavilion heightens perception. It demands attention, slowness, and presence.

This emphasis on perception situates the Pavilion within a broader understanding of architecture as imagination. Mies does not impose a fixed narrative or symbolic reading; instead, he allows space to remain open to interpretation. The water mirrors extend the architecture visually, reflecting both the building and the landscape, and reinforcing the sense of infinity and continuity. Architecture becomes inseparable from its surroundings, from the body that moves through it, and from the time it takes to be experienced. In this sense, the Pavilion operates as both architecture and sculpture—an artwork composed not of form alone, but of light, material, and movement.

At the same time, the Pavilion carries cultural and historical meaning. As a national representation, it projected an image of Germany as rational, progressive, and intellectually disciplined. Yet this identity was communicated not through monumentality or symbolism, but through restraint, abstraction, and order. Architecture became a language capable of expressing values without words. The Pavilion tells a story, not by narrating history explicitly, but by embodying a way of thinking about space, culture, and modern life.

Ultimately, Mies was not interested in creating a neutral container for art. The Barcelona Pavilion is itself an art piece—one that holds other artworks while asserting its own presence. It demonstrates that architecture can transcend function and become thought made space. Through structure, material, and proportion, Mies introduces an architectural ethos grounded in clarity, perception, and human experience. The Pavilion is not only a building, but an introduction: to Mies van der Rohe’s work, to modern architecture as continuity, and to architecture as an imaginative act that exists through time.

That is architecture.

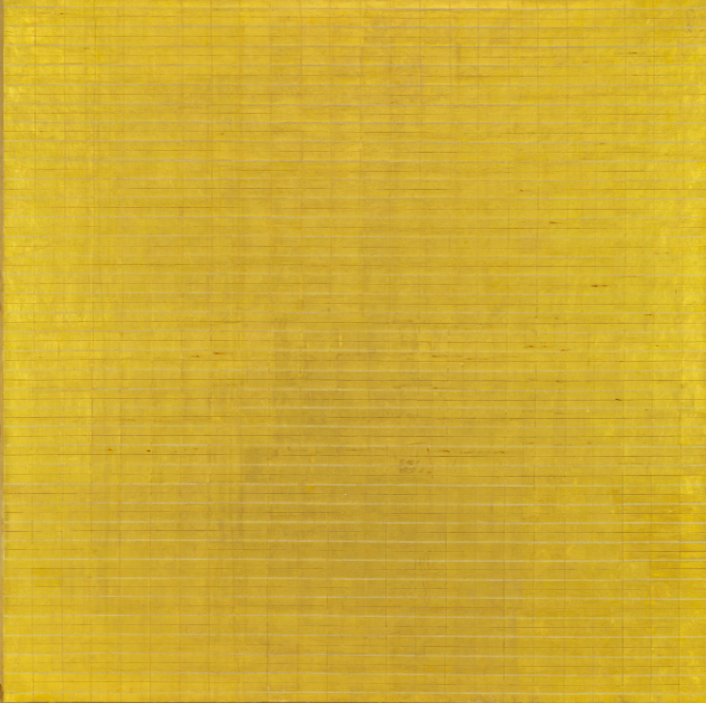

Agnes Martin. Friendship. 1963. Gold leaf and oil on canvas,190.5 × 190.5 cm.

In Friendship (1963), Agnes Martin constructs a field of quiet order where form withdraws in order to be felt. The gold-leaf surface, delicately scored by hand, resists spectacle and instead produces a condition of sustained attention. The grid—barely perceptible, never dominant—operates not as a compositional device but as an underlying structure, allowing light, rhythm, and proportion to define the experience.

This logic closely parallels the spatial philosophy of Mies van der Rohe, where structure is never ornamental but essential, and where material, proportion, and light are allowed to speak without mediation. As in Mies’s architecture, Martin’s order is not imposed; it is revealed through repetition and restraint. The grid functions like a tectonic system: silent, rigorous, and generative, holding the work together while remaining almost invisible.

Gold, traditionally associated with transcendence, is here stripped of symbolism and treated as material presence. Its luminosity recalls the reflective surfaces of marble, glass, and water in Mies’s spaces, where light becomes an active element and perception unfolds over time. There is no focal point, no hierarchy—only continuity and balance.

Friendship proposes a world reduced to essentials, where clarity does not eliminate depth, and simplicity becomes a form of precision. Like Mies’s architecture, the painting is not an image to be consumed, but a space to be inhabited—an experience shaped by stillness, proportion, and the discipline of restraint.

1. Curtis, William J. R. Modern Architecture Since 1900. 3rd ed. London: Phaidon Press, 1996. 2. Frampton, Kenneth. Modern Architecture: A Critical History. 4th ed. London: Thames & Hudson, 2007. 3. Harvard University. The Architectural Imagination. HarvardX Online Course. Cambridge, MA, 2016. 4. Mies van der Rohe, Ludwig. Barcelona Pavilion. Barcelona: Fundación Mies van der Rohe, 1986. 5. Mies van der Rohe, Ludwig. “Working Theses.” In Theories and Manifestoes of Contemporary Architecture, edited by Charles Jencks and Karl Kropf, 159–161. Chichester: Wiley-Academy, 1997. 6. Norberg-Schulz, Christian. Genius Loci: Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture. New York: Rizzoli, 1980. 7. Pallasmaa, Juhani. The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses. Chichester: Wiley, 2005. 8. Schulze, Franz, and Edward Windhorst. Mies van der Rohe: A Critical Biography. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012.